Introduction

First, let us define “computers” as any machine that can compute.

At first, analog machines were used. For example, electronic amplifiers can be used to perform integration, differentiation, root extraction, compute logarithm.

Analog computers played a significant role in history, but they have the disadvantage that noise can perturb the computation and lead to errors.

Digital computers later replaced analog ones and became mainstream. Any voltage within a range can be interpreted as a specific value. This makes digital computers much more resilient to errors.

Why base 3?

What is a numbering system?

Today, there are two numbering systems:

- decimal : used to represent numbers on a daily basis, count by hands

- binary : used by a (very) large majority of computers

The general formula to encode a number looks like this: $$ x = \sum_{i = 0}^N d_i r^i $$

Where:

- $d_i$ a factor for the $i\text{-th}$ power

- $r$ is the base (for instance 2 for the binary system)

Let us give some examples:

- in decimal (base 10), we read a number as follows:

$$ 19 = 1 * 10^1 + 9 * 10^0 = 10 + 9 $$

Here $r = 10$, $d_0 = 0$, $d_1 = 1$.

- in binary (base 2), the same number is represented as:

$$ 19 = 1 * 2^4 + 0 * 2^3 + 0 * 2^2 + 1 * 2^1 + 1 * 2^0 = 16 + 2 + 1 = 10011 $$

As we can see with those examples, the binary system uses more digits than the decimal system. But the decimal system needs to be able to produce 10 different values, instead of just two for the binary system.

We could ask ourselves what is the best, most efficient numbering system. But how do you measure the cost of a numeric representation?

Is there an optimized numbering system?

You cannot simply count digits, because then the bigger the numbering system the better. For example, you could represent 542,978 on a base 1,000,000 system. This way, you would have only 1 digit. But you would also have to recognize 1,000,000 different values for each digit, which might not be that easy, nor reliable. On the other hand, nothing prevent you from using a base 1 system to store the value 542,978. You would only have to recognize if the digit value is 0 or 1, but you would need at least 542,978 digits to store the entire value, which does not seem very efficient.

By the way, this is why the base 2 system is convenient. It can represent any number using a relatively low numbers of digits, and recognizing if the value of the digit is 0 or 1 is easy, and components to build a computer using such a system are cheap.

What we understand is that there is a tradeoff between the number of digits to use to store values and the values that each of the digits can take. Let us give names to those two things:

- $r$ is the base, the number of values per digit

- $w$ is the number of digits

In order to optimize the numbering system, we want the base to be as low as possible as well as the number of digits to store a fixed value, for example 1,000,000. We can try to optimize the product of those two values:

$$ r^* = \argmin_{r, w} rw $$

With keeping the following value constant (which represents the maximum value that can be stored):

$$ a = r^w $$

We can rewrite the second equation as:

$$ w = \frac{\ln a}{\ln r} $$

And use this value in the first equation:

$$ r^* = \argmin_{r, w} \text{ } rw \Leftrightarrow \argmin_r \text{ } \ln a \frac{r}{\ln r} $$

The term $\ln a$ is constant, so we can discard it, it won’t change the minimum of the expression:

$$ r^* = \argmin_r \frac{r}{\ln r} $$

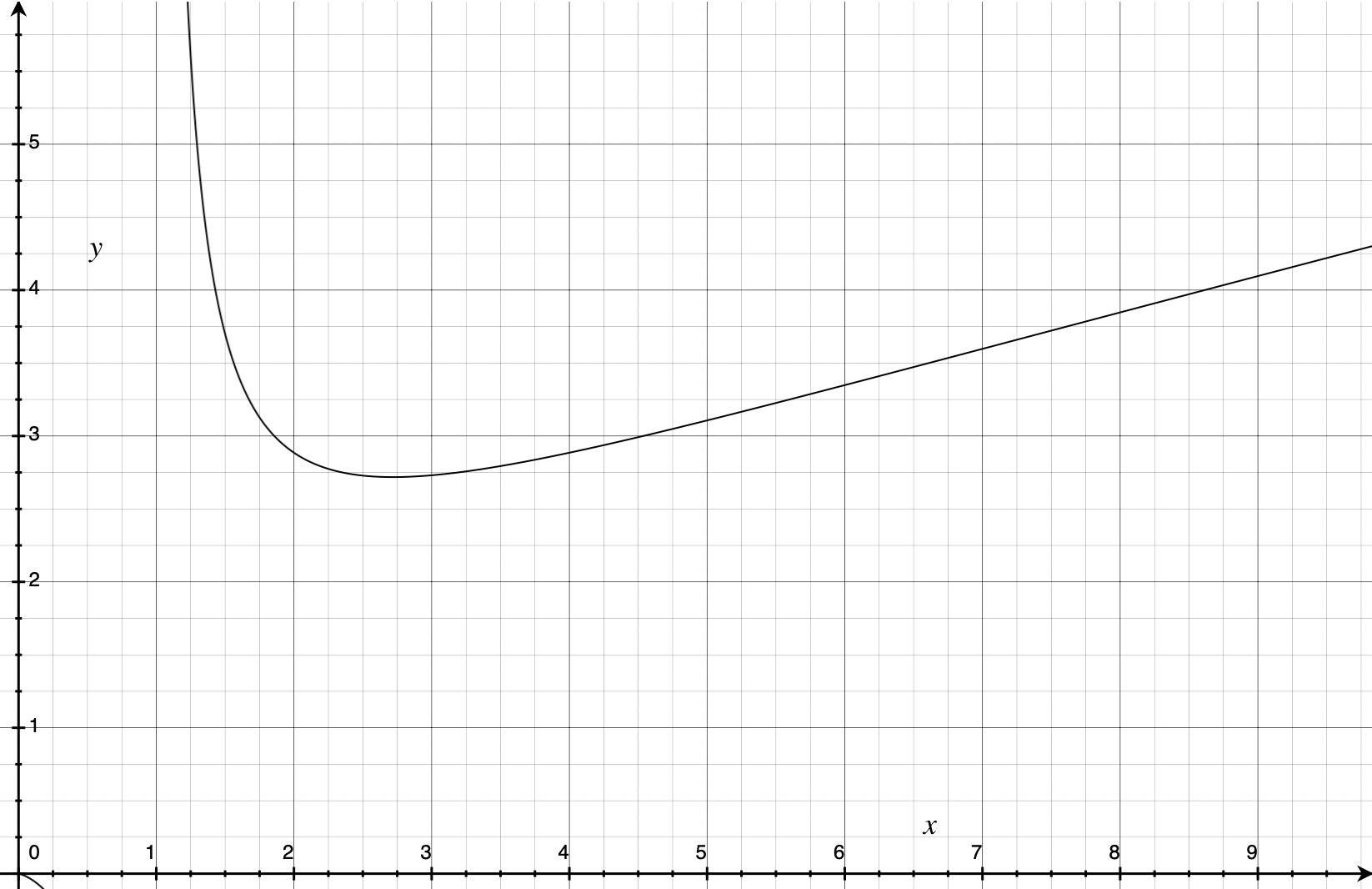

Which looks like this on a plot:

The minimum of the function seems to reached between 2.5 and 3. The exact value is given by the following formula:

$$ r^* = \argmin_r \frac{r}{\ln r} \Leftrightarrow (\frac{r}{\ln r})’ = 0 \Leftrightarrow \frac{1}{\ln r} - \frac{1}{(\ln r)^2} $$

$$ \frac{1}{\ln r} - \frac{1}{(\ln r)^2} \Leftrightarrow \frac{1}{\ln r} = \frac{1}{(\ln r)^2} \Leftrightarrow \ln r = (\ln r)^2 $$

Which is true for:

$$ \ln r = 1 \Leftrightarrow r = e \simeq 2.718 $$

Assuming that we need to represent numbers from 0 to 999,999 we can compute the product $rw$ for different base values:

- base 2 : $rw = 2 * \frac{\ln 999999}{\ln 2} \simeq 2 * 20 = 40$

- base 10 : $rw = 10 * \frac{\ln 999999}{\ln 10} \simeq 10 * 6 = 60$

- base $e$ : $rw = e * \frac{\ln 999999}{\ln e} \simeq e * 14 = 38.056$

- base 3 : $rw = 3 * \frac{\ln 999999}{\ln 3} \simeq 3 * 13 = 39$

$e \simeq 2.718$ is closer to three, which is confirmed by the value of the $rw$ product which is lower for base 3 than for base 2 or 10, making it the best system according to our hypothesis.

This is why at the early stages of computer science, the base 3 system attracted many computer designers.

History

The first working ternary computer ever built was in USSR during the cold war. A few dozens machines were built, but the ternary system faded away gradually, because reliable three-state devices were harder to build than two-state devices.

How to program using base 3

Now that we understand why base 3 numbering system might be a good choice for storing numbers, we need to introduce the ternary logic: how to add, subtract, multiply, and basically perform any operation a modern computer can perform.

In the next parts, we will talk exclusively about “balanced ternary” which is ternary digits or “trits” that can take values:

- -1

- 0

- 1

Those values can easily be mapped to boolean values according to the following table:

| Truth values | Balanced ternary values | Notations |

|---|---|---|

| False | -1 | - |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 |

| True | 1 | + |

A bit of logic

Half-adder & full-adder

When we want to perform any operation on numbers, whether they are binary numbers or ternary numbers, we first need to be able to perform those operations on single digit.

There are two different devices for the addition operation:

- the half-adder: performs the operation on 2 digits

- the full-adder: performs the operation on 2 digits and the carry

Addition, increment & decrement

The first and simplest operation is the increment and decrement, which means adding 1 or subtracting 1 to any number. It is widely used even in high level programming languages:

variable += 1

To increment a number, we simply add 1 to the least significant digit, regardless of the base system. Let us look at what it means in ternary logic with the simple $5 + 1 = 6$ example. In ternary, the sum would look like this:

$$ \begin{matrix} & 1 & {-1} & {-1} \\ + & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ = & 1 & {-1} & 0 \end{matrix} $$

Let’s take a slightly more complex example, $7 + 1 = 8$, where the least significant trit will change because of the increment:

$$ \begin{matrix} & 1 & {-1} & 1 \\ + & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ = & 1 & 0 & {-1} \end{matrix} $$

As we can see, adding 1 to the least significant trit that is already 1 makes it goes to -1 which is exactly what we already do in base 10, when performing: $9 + 1 = 10$, the least significant digit becomes 0 (the lowest value a base 10 digit can take) and the next increases by 1.

Likewise, if we need to decrement, we can just add $-1$ to the number. The logic is exactly the same, in reversed order.

In order to understand how we compute addition on a computer, let us define the half-adder and full-adder a bit more. When we perform the following addition:

$$ 4 + 19 = 23 $$

We usually do it from right to left, from the least significant digits to the most significant digits. So we start with $9 + 4$ and it gives us two results:

- the sum: the digit that will take place at the same position than the two digits we added together (here the least significant digit), it is the result of the sum of the two digits modulo the base value

- the carry: if the sum of the two digits is greater than the maximum value authorized by the base system we chose, we need to carry some information to the next digit, is it the result of the eulerian division of the sum of the two digits by the base value

In our case, the sum is $(4 + 9) \mod 10 = 3$ and the carry is $(4 + 9) // 10 = 1$.

The half-adder is the device that is able to compute those two values for each combination of trit addition:

| a | b | sum | carry |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | + | - |

| - | 0 | - | 0 |

| - | + | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | - | - | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | + | + | 0 |

| + | - | 0 | 0 |

| + | 0 | + | 0 |

| + | + | - | + |

We notice something interesting here, the carry is almost always equal to 0 except when a and b are equal, then it is equal to a and to b.

This specific operation is called consensus. It is possible to build a device that does only this and thus we will consider it an elementary operation as + or -.

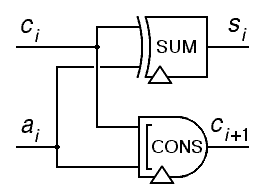

To build a half-adder, here is the device we need:

This is going to perform the two operations we talked about, computing the sum and the carry:

- $s_i = a_i + c_i$ in the notation of the picture (where $c_i$ is the carry of the previous operation, but it could also be the trit of another number we want to add)

- $c_{i + 1} = \text{consensus}(a_i, c_i)$

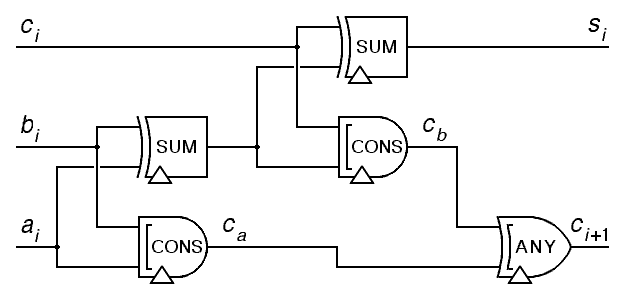

Once we have a half-adder, we can use two of them to build a full-adder, which looks like this:

As we can see on the picture, the first half-adder computes the intermediate sum $s_i$ and carry $c_a$ of the $a_i, b_i$ trits. The second half-adder computes the sum $s_i$ and carry $c_b$. In the end, the “anything” operation is used to combine both carries $c_a, c_b$. The anything operation returns 0 if both inputs are 0 or if they disagree (one is + and the other is -). It returns + or - if both inputs agree or if one is + or - and the other is 0.

Comparison

When programming, we often a way to write conditional code, a code that will be executed only if certain conditions are met.

In order to do that, we need to be able to compare numbers. The elementary comparison is the comparison to 0, because if you need to compare two numbers $a, b$ you can just subtract $b$ from $a$ and compare the result to 0 to know which one is greater.

In binary, we would have a sign bit, a bit that is exclusively dedicated to indicate the sign of the number represented.

In balanced ternary, we encode negative numbers using the same system as positive numbers. The sign of the number is the sign of the most significant trit that is not 0.

Let us see some examples:

- $-5 = - + +$

- $2 = 0+-$

- $6 = +-0$

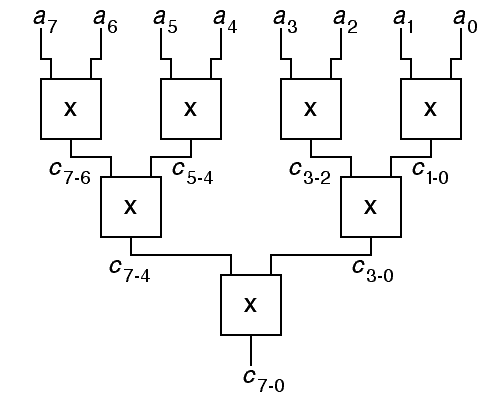

In order to perform this operation, we need a device that is able to compare trits for the whole number representation. This is what it would look like for a 8-trit representation system.

Each “X” component is a sign comparison. The truth table of such a component looks like this:

| Sign comparison | a0 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | 0 | + | ||

| - | - | - | - | |

| a1 | 0 | - | 0 | + |

| + | + | + | + |

Here $a_0$ and $a_1$ are both trits that are being compared. $a_1$ is more significant than $a_0$. We notice that the sign of $a_1$ is chosen every time it is not 0. In this case, the sign of $a_0$ is chosen.

The meaning of the result is understood as follows:

- $+$ means $>$

- $0$ means $=$

- $-$ means $<$

The complexity of the comparison is $O(\log n)$ with $n$ being the number of trits.

Multiplication

To conclude this part about logic, let us discuss the other main operation that we need to be able to perform when coding: multiplication.

There are two types of multiplication:

- multiplication by a constant

- multiplication of two variables.

For both operations, we will consider base 27. Why base 27? Because it corresponds to $27 = 3^3$ which is the number of values you can represent using 3 trits. In balanced ternary, we can store values from -13 to 13, which is 13 + 13 + 1 (zero) = 27 different values. It is the equivalent of base 16 (hexadecimal) in binary notation.

When we want to multiply a variable by a constant in base 27, we need to be able to perform the multiplication for all numbers from -13 to 13, in balanced ternary. Let us show how we can perform some of those multiplications optimally:

- 0: $a \times 0 = 0$, the easiest one, obviously

- 1: $a \times 1 = a$, also not too difficult

- 2: there are two ways of performing this operation:

- $a \times 2 = a \times 3 - a = a «_3 1 - a$ where $«_3$ is a trit shift to the left, so basically a shift and a subtraction

- $a \times 2 = a + a$ which is an addition, that we already know how to do

- 3: because 3 corresponds to the base we are using, we can simply shift trits to the right (in the direction of the most significant trit) $a \times 3 = a «_3 1$

- 4: $a \times 4 = a \times 3 + a = a «_3 1 + a$ which is a shift and an addition

- 5: $a \times 5 = a «_3 1 + 2 \times a$ where we already solved $2 \times a$

- 6: $a \times 6 = (a \times 2) \times 3 = (a \times 2) «_3 1$

- 7: $a \times 7 = (a \times 6) + a$

- 8: could be done in two different ways

- $a \times 8 = (a \times 9) - a = (a «_3 2) - a$ but the subtraction might create what is called overflow, which is when the result needs more trits than the two input of the operation, it is a bit more complicated to detect it on a subtraction than on an addition

- $a \times 8 = (a \times 2) \times 4$ where we know how to perform both multiplication already

- 9: $a \times 9 = a «_3 2$

- 10: $a \times 10 = (a \times 9) + a$

- 11: $a \times 11 = (a \times 9) + (a \times 2)$ where we know how to perform both operations already

- 12: $a \times 12 = (a \times 3) \times 4$

- 13: $a \times 13 = (a \times 9) + (a \times 4)$

For negative constants, multiplying is basically multiplying by the same positive constant and reverse all trits, because $-21 = -(21) = - (+ - + 0) = - + - 0$.

The algorithm to multiply two variables requires a loop because we will compute multiple times a base 27 multiplication as we did with the constants.

Here is the C code for the algorithm, as given by Douglas Jones in his goldmine blog:

balanced int times( balanced int a, balanced int b ) {

unsigned int prod = 0;

while (a != 0) {

unsigned int p; /* the partial product */

switch (a ^ 0v0) {

case -13: p = (b <<3 1) + b;

p = (b <<3 2) + p;

prod = (prod <<3 3) - p; break;

case -12: p = (b <<3 1) + b;

p = (p <<3 1);

prod = (prod <<3 3) - p; break;

...

case 12: p = (b <<3 1) + b;

p = (p <<3 1);

prod = (prod <<3 3) + p; break;

case 13: p = (b <<3 1) + b;

p = (b <<3 2) + p;

prod = (prod <<3 3) + p; break;

}

a = a >>3 3;

}

return prod;

}

Where $«3$ in the code is the ternary shift operator.

As we can understand, we are sequencing the multiplication by 3-trit bloc, from the most significant bloc to the last.

Advantages

We saw how to operate some basics operations of a ternary computing system. We now need to ask ourselves what advantages does it have compared to the binary system.

It has many, here are some of them:

- negative numbers: as we saw, representing negative numbers is easy using balanced ternary because it doest not require having a sign trit, as in binary

- circuit complexity: the limiting factor in the number of transistors on a specific area is not the size of the transistors themselves but the circuits they require to be connected together. Increasing the number of transistors increases rapidly the circuit complexity. With ternary transistors, the same computing power would be reached using less transistors, allowing for more transistors per surface unit, even if ternary transistors might be larger than binary transistors

- theoretical optimum: as demonstrated at the beginning of this article, base 3 is closer to the theoretical optimum of the $rw$ product

Conclusion

As we saw during this article, the ternary system has some advantages over the binary system. It is closer to the optimum in terms of circuit complexity.

Unfortunately for us, it is very likely that we will see ternary computers in the future. Not because it is unfeasible, but because it would require us to rewrite the whole tech stack modern computer science is based upon. From compilers to deep learning frameworks, we would have to adapt everything to ternary computers.

Of course, it might not be impossible to create so-called ASIC (Application Specific Integrated Circuit) that would rely on ternary transistors, and allowing them to handle some of the processing.

To conclude, I recommend to anyone interested in ternary computing to read the very nice blog by Douglas Jones that I based some of my article from: