When training models, we sometimes encounter strange cases. For example, an obvious sample that is misclassified.

This makes us wondering how come a model that is apparently doing ok on a whole benchmark, can fail at such an easy case. And it makes us realize that our model, or our benchmark, might not be as reliable as we thought.

Which is very scary.

In this article, we are going to talk about how to understand, what the model is actually learning, on what kind of features it might be relying to to achieve the task that we are training it for. The difficult thing is that a model is made up millions, and now very often billions of parameters, so looking at them each is not an option.

In this article, I am going to look at a model that we are working with for webpage classification at Outgoing. It is a fine tuned version of MarkupLM, a model developed by Microsoft a few years ago that is doing quite well on markup related tasks.

The base model is accessible on Huggingface : https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/model_doc/markuplm

The Model

HTML

Token count

A first question is why do we need specific models for structured data such as HTML, which is based on XML.

Let’s take a concrete example. Consider the following HTML snippet :

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>This is a test article</title>

</head>

<body>

<div class="article">

<h1>This is a test article</h1>

<p>This article is for testing purposes.</p>

<p>It contains multiple paragraphs to simulate a real article.</p>

<p>The content here is purely fictional and meant for demonstration.</p>

</div>

</body>

</html>

It contains very little information. Yet let’s see how many tokens would be used if we sent it to an LLM :

# We import the AutoTokenizer class from Huggingface

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

# We load the GPT2 tokenizer

t = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained('gpt2')

# We read the content of the HTML code above

content = open('data/html/article.html').read()

# We tokenize the content of the HTML code

tokens = t.encode(content)

# We print the number of tokens

print(len(tokens))

This code loads the GPT2 tokenizer, tokenizes the HTML code and then prints the number of tokens. The number is 168.

As a baseline, let’s compare with the raw text contains in the HTML document :

# We import the AutoTokenizer class from Huggingface

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

# We load the GPT2 tokenizer

t = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained('gpt2')

# We read the text content of the document

content = """This is a test article

This is a test article.

This article is for testing purposes.

It contains multiple paragraphs to simulate a real article.

The content here is purely fictional and meant for demonstration.

"""

# We tokenize the content of the HTML code

tokens = t.encode(content)

# We print the number of tokens

print(len(tokens))

This is 44 tokens, 4 times less !

To understand what is happening, let’s have a look at what gets tokenized in the document :

# Reusing the tokens variable from the tokenized document

for tok in tokens[:20]:

print(f"[{tok:5d}] {t.decode(tok)}")

which gives :

[ 27] <

[ 0] !

[18227] DO

[ 4177] CT

[ 56] Y

[11401] PE

[27711] html

[ 29] >

[ 198]

[ 27] <

[ 6494] html

[42392] lang

[ 2625] ="

[ 268] en

[ 5320] ">

[ 198]

[ 27] <

[ 2256] head

[ 29] >

[ 198]

As we can see, every character used to open or close a tag is one single token, the same goes when an attribute is defined. Another example, take this link :

<a class="link" href="https://google.com/?q=test">My test link</a>

It requires 24 tokens to be encoded where :

[ 27] <

[ 64] a

[ 1398] class

[ 2625] ="

[ 8726] link

[ 1] "

[13291] href

[ 2625] ="

[ 5450] https

[ 1378] ://

[13297] google

[ 13] .

[ 785] com

[20924] /?

[ 80] q

[ 28] =

[ 9288] test

[ 5320] ">

[ 3666] My

[ 1332] test

[ 2792] link

[ 3556] </

[ 64] a

[ 29] >

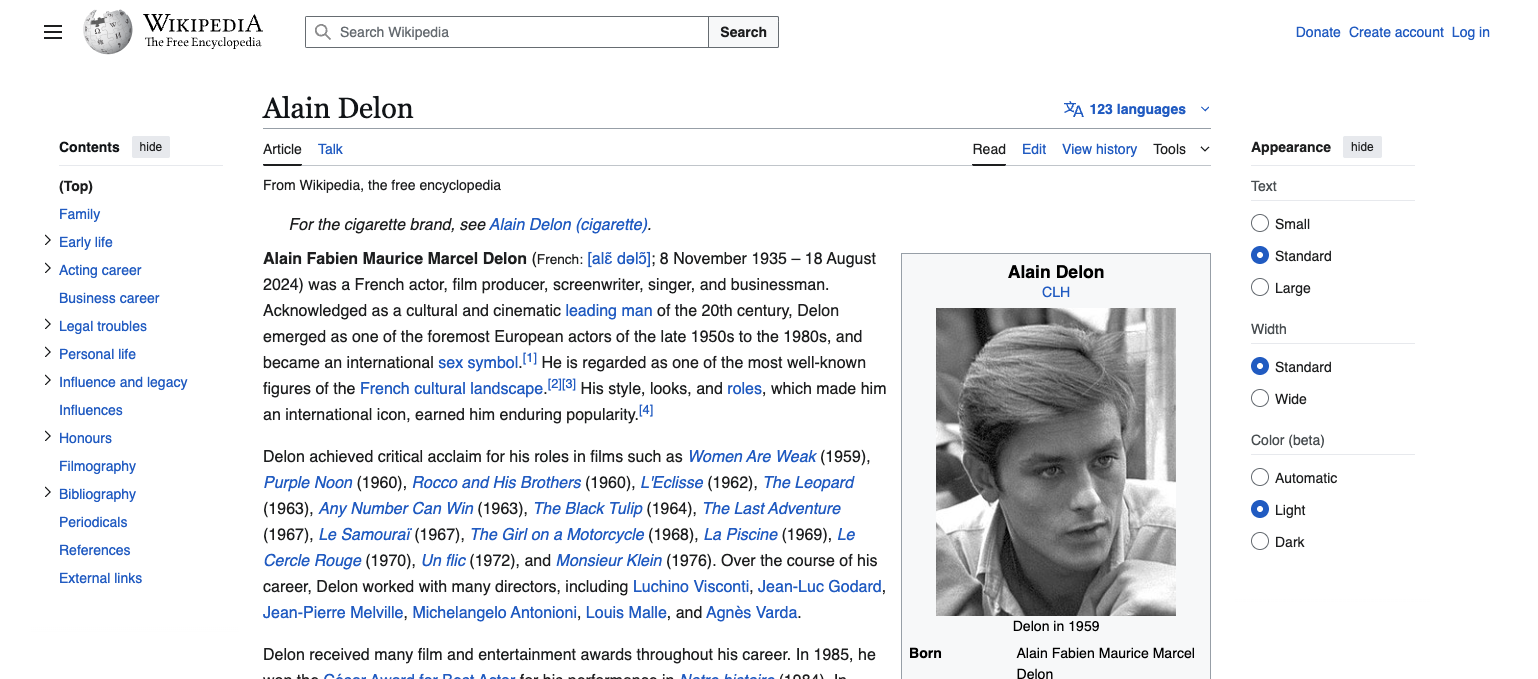

To understand why this can be a problem, we can count the number of links on a Wikipedia page. For example the page about the french actor Alain Delon (https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alain_Delon). It contains almost 9500 links. Now that we know that our small link requires 24 tokens to be encoded (and it has only one attribute on top of the href which is the class, and a relatively small text content), it means that just to encode the links on the Alain Delon’s Wikipedia page, it would take 228.000 tokens, which is biggest than Claude models’ context window ! So we would not be able to encode the links from the page, let alone the content, and the rest of the DOM tree…

Of course this is an extreme example, Alain Delon has one of the biggest Wikipedia’s pages, and not all webpages are going to consume that many tokens. But still, the structure of HTML documents makes them big for regular tokenization methods.

Structure

On top of that, the HTML conveys a specific structure. Nodes are defined from parents to children, and not all nodes are connected. This is very specific. Regular LLMs connect each token from the input data to every other tokens through the Attention matrix. But this is very inefficient (it requires matrices that grow quadratically with the number of input tokens).

Let’s have a look at the following screenshot :

The buttons at the top right corner are relative to the website itself, not the content of the page. The same goes for the right panel. They are not linked to the article content. If we are trying to understand what is in the page, extract information out of it or classify it, we might not want to treat all DOM tree nodes equally, and for sure not connect them all.

Finally, let’s consider the menu of the page (top right corner) :

<li id="pt-sitesupport-2" class="user-links-collapsible-item mw-list-item user-links-collapsible-item">

<a data-mw-interface href="https://donate.wikimedia.org/?wmf_source=donate&wmf_medium=sidebar&wmf_campaign=en.wikipedia.org&uselang=en" class="">

<span>Donate</span>

</a>

</li>

<li id="pt-createaccount-2" class="user-links-collapsible-item mw-list-item user-links-collapsible-item">

<a data-mw-interface href="/w/index.php?title=Special:CreateAccount&returnto=Alain+Delon" title="You are encouraged to create an account and log in; however, it is not mandatory" class="">

<span>Create account</span>

</a>

</li>

<li id="pt-login-2" class="user-links-collapsible-item mw-list-item user-links-collapsible-item">

<a data-mw-interface href="/w/index.php?title=Special:UserLogin&returnto=Alain+Delon" title="You're encouraged to log in; however, it's not mandatory. [o]" accesskey="o" class="">

<span>Log in</span>

</a>

</li>

They follow the exact same node structure (/li/a/span) and they even have the same class. This is something that we would like our model to understand.

We now understand why a regular linear LLM is not going to be the optimal solution to HTML processing.

MarkupLM

MarkupLM is based on BERT, a famous model released by Google in 2018. The difference with raw BERT lies in the way it encodes the content of the HTML document. It does not tokenize the raw content like a regular LLM would do. Instead, it uses 3 types of embeddings :

- the text embeddings, just like a regular language model

- the xpath embeddings, which are a combinations of two embeddings :

- the xpath tag embeddings

- the xpath subscript embeddings

To illustrate how MarkupLM handles the input, let’s reuse the toy example we introduced earlier :

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>This is a test article</title>

</head>

<body>

<div class="article">

<h1>This is a test article</h1>

<p>This article is for testing purposes.</p>

<p>It contains multiple paragraphs to simulate a real article.</p>

<p>The content here is purely fictional and meant for demonstration.</p>

</div>

</body>

</html>

I will use this to illustrate parts of the code.

The code is available in both the Huggingface transformers’ repository and the Microsoft repository. For feature extraction, I think the HF repo is easier to understand, but for the model itself, the Microsoft code is easier to understand, so I will do a back and forth between the two, but of course the logic is exactly the same, only implementation details differ.

MarkupLMFeatureExtractor

The first step is to extract features out of the DOM tree. The Huggingface’s MarkupLM implementation uses a class named MarkupLMFeatureExtractor, which extract two things from the DOM tree :

- the nodes : the text content of the DOM tree nodes

- the xpaths : the xpath of the DOM tree nodes (only the nodes that contain text)

So for the HTML page above, the result of calling the MarkupLMFeatureExtractor would be :

{

"nodes": [

[

"This is a test article",

"This is a test article",

"This article is for testing purposes.",

"It contains multiple paragraphs to simulate a real article.",

"The content here is purely fictional and meant for demonstration."

]

],

"xpaths": [

[

"/html/head/title",

"/html/body/div/h1",

"/html/body/div/p[1]",

"/html/body/div/p[2]",

"/html/body/div/p[3]"

]

]

}

It is a dictionary containing two keys and each key contains a list of list. The first dimension is the batch and the second dimension is the actual nodes and their xpath. So the first node extracted from the DOM tree is the paragraph containing Countries of the World: A Simple Example | Scrape This Site | A public sandbox for learning web scraping and located at xpath /div/title/p.

From this, the embeddings will be computed.

Embeddings

There are two classes needed to compute the embeddings :

- the regular text embeddings, MarkupLM uses classical word + positional embeddings, so I won’t dig into the details here

- the xpath embeddings, MarkupLM computes two embeddings for xpath :

- xpath tag embeddings : the embeddings of the components of the xpath, for example div, body, a, section…

- xpath subscript embeddings : the embeddings of the number that sometimes follows a component of the xpath, indicating that there are several nodes that have the same xpath, and an index is used based on the order they are defined in the DOM tree

For the xpath embeddings, MarkupLM extracts both the sequence of tags of the xpath string and the subscript sequence. For the node with text Andorra and xpath /div/body/div/section/div/div[2]/div[1]/h3 it looks like :

# text is the HTML content, fe is an object of type MarkupLMFeatureExtractor

# and the index in t[2] points to the node containing "This article is for testing purposes."

print([t[2] for t in fe.get_three_from_single(text)])

[

'This article is for testing purposes.', # The text of the node

['html', 'body', 'div', 'p'], # The xpath decomposed

[0, 0, 0, 1] # The subscripts, 0 because html is not followed by a number, 1 because p is followed by a number

]

Once we have both sequences, we are going to pad them to the maximum depth so that all sequences have the same size. This process is no different from what is sometimes being done with text, when we have to work with variable size text strings.

And finally we embed both sequences. Each component of the xpath is embedded (the tag and the subscript are processed individually at this stage), which gives two vectors of size $(n, d)$ where $n, d$ are the length of the sequence and the dimension of the embedding space respectively.

The two sequences are then summed and passed through a linear layer to get the final xpath embedding.

Finally, the token embeddings, the positional embeddings and the xpath embeddings are all summed.

The code can be found here, inside the MarkupLMEmbeddings and XPathEmbeddings classes : https://github.com/huggingface/transformers/blob/v5.0.0rc1/src/transformers/models/markuplm/modeling_markuplm.py#L95

Processor

When using MarkupLM, we don’t have to work with the classes I talked about above, HF offers a class that processes the HTML for us and makes it ready for the model to work : MarkupLMProcessor. This class returns an object that contains the following tensors :

- input_ids

- token_type_ids

- attention_mask

- overflow_to_sample_mapping

- xpath_tags_seq

- xpath_subs_seq

We recognize the sequences we just talked about.

Let’s have a look at the inner tensors of this object :

# Import the MarkupLMProcessor class

from transformers import MarkupLMProcessor

# Load the processor

p = MarkupLMProcessor.from_pretrained('microsoft/markuplm-base')

# Process our HTML string

tensors = p(html_strings=[text], truncation=True, max_length=512, padding='max_length', return_tensors='pt')

# Display the shapes of the token ids and the xpath tag ids

print(tensors['input_ids'].shape, tensors['xpath_tags_seq'].shape)

# torch.Size([1, 512]), torch.Size([1, 512, 50])

And now let’s display each text token along with its xpath tokens :

[This] [109, 104, 200] # /html/head/title

[ is] [109, 104, 200]

[ a] [109, 104, 200]

[ test] [109, 104, 200]

[ article] [109, 104, 200]

[This] [109, 25, 50, 98] # /html/body/div/h1

[ is] [109, 25, 50, 98]

[ a] [109, 25, 50, 98]

[ test] [109, 25, 50, 98]

[ article] [109, 25, 50, 98]

[This] [109, 25, 50, 148] # /html/body/div/p[1]

[ article] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ is] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ for] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ testing] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ purposes] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[.] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[It] [109, 25, 50, 148] # /html/body/div/p[2]

[ contains] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ multiple] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ paragraphs] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ to] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ simulate] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ a] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ real] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ article] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[.] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[The] [109, 25, 50, 148] # /html/body/div/p[3]

[ content] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ here] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ is] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ purely] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ fictional] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ and] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ meant] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ for] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[ demonstration] [109, 25, 50, 148]

[.] [109, 25, 50, 148]

Even though the xpath tokens are ids and we cannot just decode them using the tokenizer (because they are encoded differently, each tag name has its id), it is easy to guess which is which :

| Xpath Tag Token ID | HTML Tag |

|---|---|

| 109 | html |

| 25 | body |

| 104 | head |

| 200 | title |

| 98 | h1 |

| 50 | div |

| 148 | p |

And the same goes for the subscript tokens :

[This] [0, 0, 0]

[ is] [0, 0, 0]

[ a] [0, 0, 0]

[ test] [0, 0, 0]

[ article] [0, 0, 0]

[This] [0, 0, 0, 0]

[ is] [0, 0, 0, 0]

[ a] [0, 0, 0, 0]

[ test] [0, 0, 0, 0]

[ article] [0, 0, 0, 0]

[This] [0, 0, 0, 1]

[ article] [0, 0, 0, 1]

[ is] [0, 0, 0, 1]

[ for] [0, 0, 0, 1]

[ testing] [0, 0, 0, 1]

[ purposes] [0, 0, 0, 1]

[.] [0, 0, 0, 1]

[It] [0, 0, 0, 2]

[ contains] [0, 0, 0, 2]

[ multiple] [0, 0, 0, 2]

[ paragraphs] [0, 0, 0, 2]

[ to] [0, 0, 0, 2]

[ simulate] [0, 0, 0, 2]

[ a] [0, 0, 0, 2]

[ real] [0, 0, 0, 2]

[ article] [0, 0, 0, 2]

[.] [0, 0, 0, 2]

[The] [0, 0, 0, 3]

[ content] [0, 0, 0, 3]

[ here] [0, 0, 0, 3]

[ is] [0, 0, 0, 3]

[ purely] [0, 0, 0, 3]

[ fictional] [0, 0, 0, 3]

[ and] [0, 0, 0, 3]

[ meant] [0, 0, 0, 3]

[ for] [0, 0, 0, 3]

[ demonstration] [0, 0, 0, 3]

[.] [0, 0, 0, 3]

Where again it is trivial to interpret the subscripts.

As we understand, every text token embedding is going to be summed with the xpath tag embedding of the node it belongs to. This is how text tokens from a similar node are going to receive the same tag and subscript embeddings, so they will be closer in the final embedding space.

But those are the ids, and not yet the embeddings, they will be translated to embeddings at the very beginning of the forward method :

def forward(

self,

input_ids: Optional[torch.LongTensor] = None,

xpath_tags_seq: Optional[torch.LongTensor] = None,

xpath_subs_seq: Optional[torch.LongTensor] = None,

attention_mask: Optional[torch.FloatTensor] = None,

token_type_ids: Optional[torch.LongTensor] = None,

position_ids: Optional[torch.LongTensor] = None,

inputs_embeds: Optional[torch.FloatTensor] = None,

output_attentions: Optional[bool] = None,

output_hidden_states: Optional[bool] = None,

return_dict: Optional[bool] = None,

**kwargs,

) -> Union[tuple, BaseModelOutputWithPooling]:

# ...

# some code before computing the embeddings

# ...

embedding_output = self.embeddings(

input_ids=input_ids,

xpath_tags_seq=xpath_tags_seq,

xpath_subs_seq=xpath_subs_seq,

position_ids=position_ids,

token_type_ids=token_type_ids,

inputs_embeds=inputs_embeds,

)

# the rest of the code ...

The self.embeddings attribute is the MarkupLMEmbeddings layer we described before.

Limitations

First, let’s talk about a fundamental limitation of the model : its context size.

Because MarkupLM is based on BERT, it has a maximum context window (the number of tokens it can accept as input) of 512, which is very low.

So when we are classifying a page, it is likely that the tokenized page is going to be too big for MarkupLM to handle, and what could be relevant information (such as the footer of the website for instance), is going to be truncated.